Wordle 362 4/6

⬜🟨🟨🟨⬜

🟨🟨🟨⬜⬜

🟩⬜🟨🟨🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 362 4/6

⬜🟨🟨🟨⬜

🟨🟨🟨⬜⬜

🟩⬜🟨🟨🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 361 5/6

⬜⬜🟨⬜⬜

⬜🟨⬜🟨⬜

⬜⬜🟨⬜🟩

🟨⬜🟩⬜🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

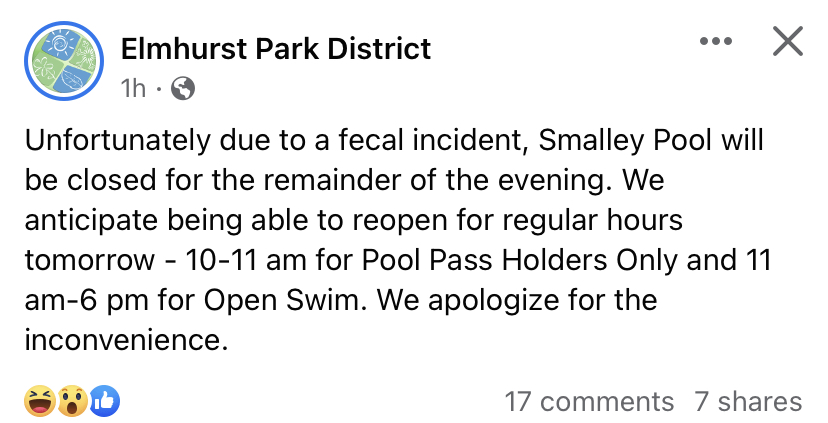

Yesterday’s hometown news. This is a big reason why I don’t miss the summer days when F would beg to go to the pool.

Helena chills after a mouthful of the ‘nip.

Forgot again yesterday. Streak back at 1. 😐

Wordle 360 3/6

🟨⬜🟨⬜🟩

⬜🟨🟨⬜🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Been falling off the low-carb wagon a lot lately. I’ve had more of these blondies than anybody really should. Need to back away.

It dawned on me last week that I forgot to join this year’s Index-Card-A-Day art challenge.

I had enjoyed last year’s challenge so much that forgetting it this year startled me. I thought about just starting it late, catching up on the first few days I missed. But it dawned on me that no, I really don’t feel like doing it this year. Too much other stuff in my orbit, mainly – but not exclusively – steering F into high school and all the things associated with that. Throw in excessive work demands and basic self-care needs and I don’t think I can fit in much more.

F did this one, again while we waited in the Portillos drive-thru line.

Wordle 358 5/6

🟨⬜⬜⬜🟨

⬜🟨🟨🟨⬜

🟨🟨⬜⬜⬜

⬜🟨🟨⬜🟨

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Blondies, based on a recipe that came with the new stand mixer.

I have really tried to love Kids in the Hall over the years, but “Doomsday DJ” is the first KITH sketch that has really clicked with me.

I have spent a lifetime trying to fit in wherever I am, and I have never felt as if I succeeded. A lifetime of feeling like an outsider, from my birth family onward, has been a lonely one.

This could be why I am so consumed with the hope that F can find her tribe in high school. Watching her navigate the painful middle school years has dredged up an awful lot of PTSD for me; reading about autistic people’s childhood experiences — many of which have echoed my own early years — has just compounded that.

I sort of transcended social groups back in my day, floating among different ones with some degree of acceptance but never really becoming that entrenched in any one. I was proud of myself for that somehow, as if it proved I was above cliquishness and the need for deep friendships. (I was brought up to believe that I could never trust anyone outside my immediate family, which I have learned the hard way is such a damaging — not to mention warped — mentality.) So why was I so deeply lonely, even despairing at times?

(This experience is echoed throughout the audiobook of Unmasking Autism that I’m working through, which has helped get me thinking so much about all this.)

College was better, I guess, where I became firmly entrenched at the student newspaper. It helped that most of us were working toward a common goal of a news career. But I still couldn’t avoid that outsider feeling there and in other contexts, like the evangelical Christian college dorm where I lived for almost 2 years and felt like the odd one out as a fat, brown, nominally Catholic person.

I never fully shook that outsider feeling through my single years, or even in my married ones. Even and especially now, in a White suburban town outside Chicago — when I once got disdainful looks from the Caucasian stay-at-home moms at F’s kindergarten playground outings as if I was merely a nanny — I get that vibe. And I am very much an outlier, politically speaking at least, at our traditional and orthodox Roman Catholic parish, where some folks will ask the priest how to get out of a COVID vaccination requirement and tell me about all the killings of January 6 rioters by Capitol Police that “the news won’t tell you about.”

I’ve reluctantly accepted my perennial sense of separateness in this world. It helps a bit that I ended up marrying someone who has experienced that same sense of never quite belonging (and admits that he, too, is likely on the spectrum), so it’s kind of a blessing that we belong to one another.

My greatest longing right now is that F has that same sense of belonging with us, too, as her loving weirdo parents. But I also yearn to have her find that beyond us in the wider world.

Wordle 357 4/6

⬜⬜🟨⬜⬜

⬜⬜⬜⬜🟩

🟨⬜🟩⬜🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Expecting emotional intelligence from people who have demonstrated a lack of it since my childhood is a lost, painful cause. I have to keep reminding myself of this.

Wordle 356 4/6

⬜⬜🟩⬜⬜

⬜⬜🟩⬜⬜

⬜⬜🟩⬜🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Random thoughts at the end of a long, exhausting work week:

As always, onward.

Wordle 355 6/6

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

🟨🟨⬜⬜⬜

⬜⬜🟨⬜🟨

🟨🟩⬜🟩⬜

⬜🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Forgot yesterday. Again. Streak back at 1.

Wordle 353 4/6

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬜🟩⬜⬜⬜

⬜🟩⬜⬜⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 352 4/6

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬜🟩🟩🟩⬜

⬜🟩🟩🟩⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 351 5/6

⬜⬜🟨⬜⬜

🟩🟩⬜🟩⬜

🟩🟩⬜🟩⬜

🟩🟩⬜🟩⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

F actually did this one while we were waiting in the Portillo’s drive-thru line after Mass. I may start outsourcing my Wordle more often.

Frannie broke in her I-escaped-middle-school gift from her Auntie Eleanor—a stand mixer—this afternoon with buttery pretzel bites.

Wordle 350 4/6

🟨⬜⬜🟨⬜

🟨🟨⬜🟩⬜

⬜🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

The Wordle is about as much as I can do half the time these days.

Only the second time I’ve done this in two.

Wordle 349 2/6

🟩⬜🟨🟨⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 347 5/6

⬜🟩🟨⬜🟨

⬜🟩🟩🟩🟩

⬜🟩🟩🟩🟩

⬜🟩🟩🟩🟩

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩

Wordle 346 4/6

⬜⬜⬜⬜⬜

⬜🟨⬜🟨⬜

🟩🟩🟨⬜⬜

🟩🟩🟩🟩🟩